Healthy Hips - this is a very common worry for parents who want to ensure they have the best information regarding their child's safety. Here, Rosie busts some of the myths and assesses what we really know on the subject.

People often ask me about the importance of a good position for their child’s hips in a carrier, having heard about “hip dysplasia” and “knee to knee”. These are good questions to consider, as there is a lot of hearsay and slightly misinformed information circulating around the internet.

I thought it would be helpful to discuss some common queries and consider what “best practice” might be. I will look at what hip dysplasia actually is and assess if narrow based carriers really are harmful to children. I will suggest some alternatives that are much more respectful of child anatomy and more comfortable for baby and parent.

1) What is hip dysplasia?

There are many terms used for this spectrum of related developmental hip problems in infants and children. These are often present at birth. Most recently the term “Developmental Hip Dysplasia” is being used, as there is evidence to suggest that while many hip disorders, (ranging from full dislocation, to unstable shallow sockets) are present at birth, some children with apparently normal hips go on to develop problems in the first year of life.

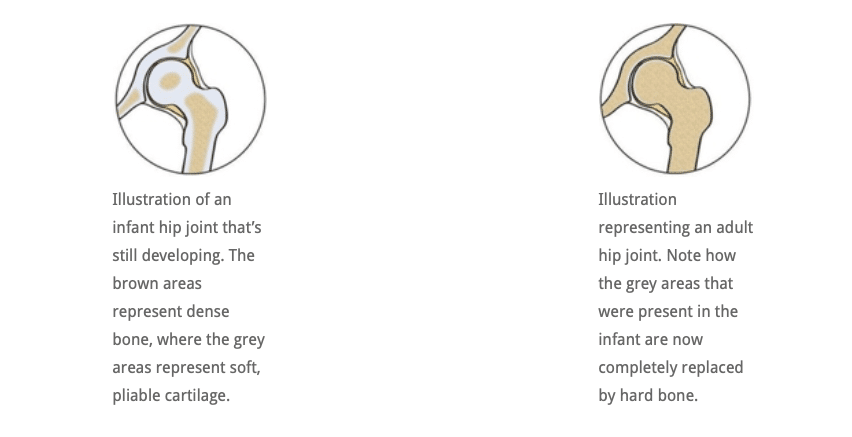

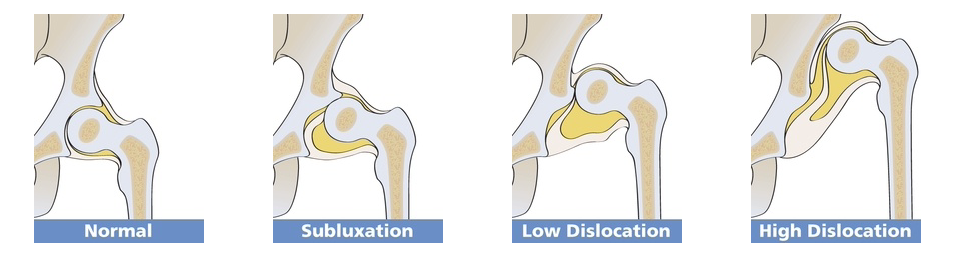

In simple terms, dysplasia means “growing abnormally”. Compared to adults, an infant’s hip sockets are made up of a greater proportion of softer, more pliable cartilage in relation to bone. This means that it is easier, anatomically, for the ball (the femoral head) to slip out of of the socket (the acetabulum) and be misaligned (subluxated) or fully dislocated. A normally formed hip joint will not encounter problems, but this softer structure, in combination with an abnormal socket shape, explains why some joints will dislocate.

In a child who has an abnormally developed hip joint, the combination of the shallow angle of the socket and the softer structure means that the ball (femoral head) is not held securely within the socket and can become misaligned and even slip out if the joint is placed under downward strain. If it does not slip back in, it is a dislocated joint and will need intervention. See the Hip Dysplasia website for more.

2) Is my child at risk of hip dysplasia?

The causes for hip dysplasia are poorly understood. There seems to be an increased risk if there is a positive family history of hip dysplasia. Female babies seem to be 4-5 times more at risk than males, and several factors in pregnancy seem to be relevant. For example,

- a tight uterus

- reduced uterine fluid that constricts the baby and prevents free fetal movement,

- breech delivery

- another condition that affects how babies lie in utero (such as fixed foot deformity)

all seem to be related to the presence of dysplasia. The left hip seems to be more frequently involved than the right. Furthermore, the growing baby is exposed to the mother’s oestrogen hormones. Oestrogen is thought to encourage ligament relaxation near the time of delivery, which may help with giving birth, but potentially may also cause the baby’s hip ligaments to be somewhat lax and increase the risk of an unstable joint.

These are not risks that a parent has any control over, clearly.

However, there are studies that strongly suggest that some cultures who swaddle their infants tightly (such as the Native American societies prior to the 1950’s, and some Japanese societies) have a far greater incidence of developmental hip dysplasia and childhood hip dislocation.

It is interesting to see that once the Najavo Indian culture, (who carried their babies tightly bound on cradle boards with their legs straightened ie extended and adducted), adopted bulky cloth nappies, the incidence of childhood hip dislocation decreased dramatically, even though they continued to use the cradle boards.

This was due to the nappies encouraging the babies’ legs to be held in a more natural flexed and abducted position (like a spread squat, as if child held on hip with legs around parent). African cultures, who do not swaddle their babies, and carry them constantly astride their backs from birth, have a very low incidence of hip dysplasia. You can read a very helpful scholarly article here for more information.

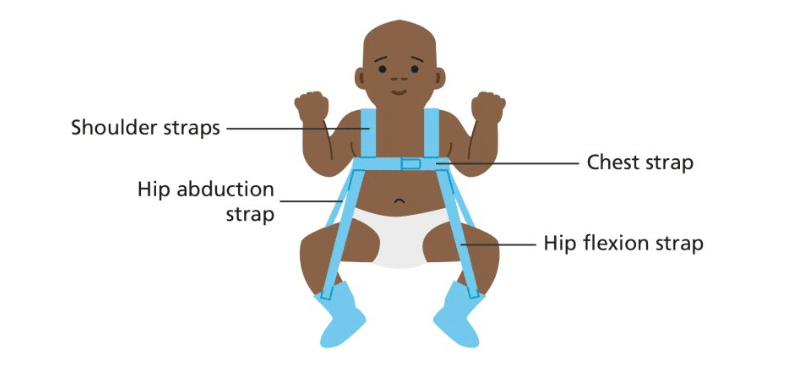

In 2015 the Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics published an article based on data from 40,000 children in Malawi and a systematic review of current evidence. “The majority of mothers in Malawi back-carry their infants during the first 2 to 24 months of life, in a position that is similar to that of the Pavlik harness. We believe this to be the prime reason for the low incidence of DDH in the country. In addition, there is established evidence indicating that swaddling, the opposite position to back-carrying, causes an increase in the incidence of DDH. If a carrying position of infants during their early months of development can reduce the incidence of DDH, then a public health initiative promoting back carrying could have significant world health and financial implications in the future management of DDH and also have potentially huge effects on the timing and severity of development of adult hip arthritis.”

“Hence it appears logical to discourage putting the baby’s legs in the extended position, and encourage keeping the baby’s hips spread apart. This latter position places the head of the femur (the ball) against the acetabulum (the socket), and encourages deepening of the socket.” (Quote from Orthoseek– a source of authoritative information on paediatric orthopaedics.)

So, a parent can potentially reduce the small risk of hip dysplasia by carefully considering some of the practices they adopt.

3) How is hip dysplasia diagnosed and treated?

Diagnosis: Most suspected cases of hip dysplasia are picked up at birth or at the six week check, by physical examination, but some cases are missed, sometimes with significant consequences. There is a strong case for routine ultrasound screening for hip dysplasia, as comprehensive ultrasound screening during the immediate newborn period has demonstrated hip laxity in approximately 15% of infants (Rosendahl K, et al. Pediatrics 1994;94:47-52)

Treatment: Mild cases can be managed by “double diapering” to keep hips in the flexed, abducted spread squat position. More severe cases may need splinting with a Pavlik harness and sometimes surgery is required. Many children respond very well to this and lead normal lives. If left untreated, and picked up later in childhood (eg a limp) developmental hip dysplasia can have chronic consequences, such differences in leg length, awkward gaits or decreased agility. Older children may even develop early arthritis of the hip. Sometimes complex surgery is needed.

4) Is there anything I can do to reduce my child’s chance of hip problems?

It isn’t fully clear exactly how large a role the choices parents make (eg swaddling, cloth nappy use, carrying in an appropriate sling) have on the likelihood of hip problems later in life. Some babies may have mild DDH at birth that is not discovered at all, and thus unwittingly benefit from good hip positioning that a wider based carrier gives, encouraging the mild laxity to self-correct. There are many cases of babies who have been found to have DDH and been advised to use a wider based carrier by their orthopaedist, and the shallowness has self corrected. Clearly, wider based carriers are beneficial.

Furthermore, by 6 months of age, the risk of hip dysplasia has largely passed, and by one year children are stronger, better developed, and able to place their hips in a healthy position themselves when required for comfort (ie pull their knees up or ask to get down), so older children are not at risk. It is young babies in the first few months of life that need more caution.

2018 update. There has been a small increase in the late diagnosis of DDH, which is thought to be possibly related to the use of tight swaddling, a technique to settle babies that has seen some resurgence recently. Firm swaddling of the lower body forces babies’ legs into prolonged positions of tight adduction and extension which can be damaging to hips that are already vulnerable. Swaddling should always be done in a hip healthy way (read more here about the late diagnosis of DDH).

It would seem sensible, therefore, at least in the early months of life, to encourage babies and small children to have their hips held in a healthy position, that is less likely to place strain on lax ligaments or possibly shallow hip sockets. A good, wide-based sling or carrier can assist with this healthy hip position. This will also be more comfortable for the child – consider perching on or astride a stool versus sitting on a chair or even in a hammock!

It is worth being aware that there is often variance in the advice orthopaedic surgeons offer, based on their depth of knowledge of babywearing. There is little formal research on the effects of slings per se in children with DDH, and much is extrapolated. The Institute of Hip Dysplasia is a helpful resource.

2024 update. There has been a lot of interest in the possibility of using cloth nappies to keep children’s hips in a wider based position. Evidence that this is helpful is lacking. This may prove a useful read, a study done into this very thing. It does recommend slings and carriers!

5) Will my narrow-based high-street carrier harm my baby’s hips?

Much debate has been held on the role that narrow -based carriers may have on the worsening of pre-existing, undiagnosed hip dysplasia, or promoting its development in normal hips. It is worth bearing in mind that few parents use narrow based carriers for any significant length of time, as they are often not especially comfy, and babies’ legs are free to move in the carrier, rather than being held forcibly in one position. Many narrow based carriers are wider than they used to be, so small babies often end up in a slightly abducted and rotated position anyway.

So the simple answer to the question is “Probably not, in the majority of cases.” This assumes your child’s hips are normal, and they are not one of the postulated 15% of infants whose condition is missed by health care professionals (however well-meaning). These children will most certainly benefit from a wider based carrier.

So you are unlikely to damage your child’s hips if they are healthy. It will be up to you to assess the risk that mild DDH may not have been identified at the routine screening, and make the choice for yourself.

These narrow based carriers usually have a particular feature of robust head and neck support. The reason for this is because a child who has unsupported legs will usually end up with an arched, over-straightened spine where their head and airway is not adequately protected. Baby’s heavy head is more likely to fall backwards, and therefore rigid neck supports are needed to keep him safe. This is in contrast witih carrying positions which do encourage the natural pelvic tuck and therefore a curved spine and baby’s head becoming self-supporting while he rests against parent (think about how you often only need to support baby’s bottom when they are sleeping on your chest or shoulder).

Parents of children with normal, non-dysplastic joints are unlikely to “cause” hip dysplasia by choosing to use one of these narrow-based slings, but these designs do not, on the whole, promote the flexed, abducted spread-squat position that seems to encourage better hip joint positioning and deeper development of the socket. A sling that supports baby’s thighs from beneath (“knee to knee”) is more likely to keep hips in this optimal position, and reduce strain on still-developing joints. It is interesting to note that the bigger brands who are well known for making narrow based carriers have begun to redesign their products to be more broad at the base and more respectful to baby anatomy.

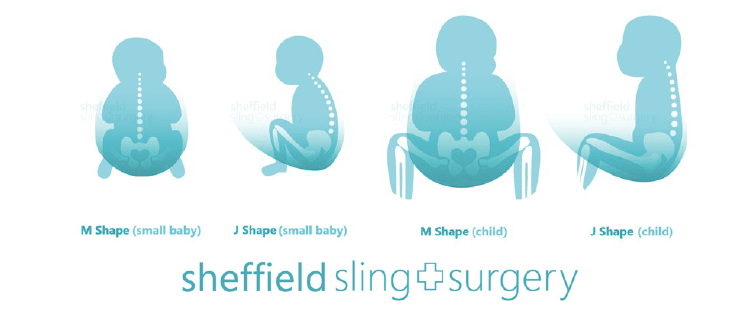

It will be no surprise then, that most professionally-trained babywearing consultants will advocate the thighs being supported right into the knee pits into an M shape, with knees held higher than the bottom (nearer to an imaginary horizontal line out from the belly button). This puts the femoral head into an ideal central position in the socket, and is the position adopted by the Pavlik Harness as you can see above.

Here is are some drawings that show the most typically seen position in a narrow based carrier, and then the ideal hip position in a sling

1) Classic high-street narrow-based carrier (red arrows). The legs are hanging downwards, entirely unsupported. The infantile hip-socket is taking the full weight of the legs and there will be a lot of unhelpful strain. It is similar to balancing on a beam at the gym with all the weight being borne on a narrow strap between the legs. Baby’s back may be straightened, meaning their head is able to fall backwards, needing rigid head and neck support.

2) A properly fitting, wide-based carrier (green arrows). Observe the M-shape that has been created, with the thighs securely supported all the way to the knees, which are held above the bottom. The hip joints are in the optimal position, and there is no weight at all dragging down on the joint. Orthopaedic consultants recommend thighs to be resting at an angle of 100 degrees from the midline.

These drawings show how there is no downward strain on the socket and the child is supported widely across a large proportion of their base. The baby is clearly seated comfortably with their weight widely distributed, and the gentle curve of their spine protected. This baby’s upper body will be supported against the parent with head resting on parent’s chest, and rigid head supports are not needed (using natural anatomical positions).

6) What slings would you recommend for healthy hip position?

All safe babywearing is to be celebrated and encouraged! Using a narrow-based carrier will not harm the majority of children (see above), so if you have one already, there are a few things you can do to improve your child’s comfort such as using a scarf tucked into the seat, as in this video. This will encourage a change of position from legs hanging straight downwards (extended and adducted) to supported knee to knee (flexed and abducted) in the M shape, as discussed above. It is, however, only a temporary solution – I would advise you to use a wider-based carrier.

To reproduce the hip-healthy M shape, when putting a child into a carrier, tilt their pelvises inwards slightly and push the feet below their bent knees upwards to encourage flexion. All babies are different, and some will naturally spread their legs more widely than others. NEVER force your baby’s legs to move into a position that does not come easily.

If you don’t yet have a sling for your baby, go for a soft one that is well designed to both promote healthy hip M-position and encourage the natural gently curved J-spine shape that young children have (rather than a tight C shape where a heavy head would be drooping down onto the chin curled over). The secondary curves begin to develop later on in life – the cervical curve when they gain head control and can lift against gravity, and the lumbar curve at the crawling/walking stage . Until then, spines should not be artificially kept straight (ie babies should avoid too much time in rigid car seats, stiff inflexible carriers, or lying supine on their backs).

It is worth remembering that well-designed slings that focus on supporting a child’s legs and curved spine can be used in a less than ideal way. It is possible to use a good tool in a less than optimum manner, especially when in a hurry, so it is worth taking your time to position the sling well and to be actively aware of your child’s hip and spine positions when putting the sling on.

Examples of suitable slings (this list is not exhaustive and is merely a guide). See your local sling meet/consultant/library for more help and advice or read our sling guide.

Stretchy wraps, Close Carrier hybrid

Ring slings or Scootababy hip carrier

Meh Dais and Half-Buckles and variants

7) What do I do when my child’s legs are too long for “knee to knee” support?

Small babies, sadly, all too soon grow into big babies, with longer legs, and can start to out-grow their slings in terms of thigh support along to the knees. And then they start to toddle! When a child can stand unaided and walk, he will have the muscle and ligament strength to bear the weight of his own legs well, so full knee-to-knee is less important for toddlers, but for smaller babies, helping to support their legs is important. You may need a wider sling, or you can adjust the one you have already with a helpful scarf – there is a great video here from Slingababy.

8) Where can I find more help and support and reading about using a sling for my child?

There are numerous resources in the UK where you can get babywearing advice and encouragement, such as your local babywearing consultant, sling meet, or sling library. The links below will help (again, not an exhaustive list!)

The Carrying Matters Sling Guide

Dr E Kirklionis’ book A Baby Wants to Be Carried is highly recommended, for its overview of the evolutionary theory behind baby carrying and the spread squat positioning.

You can read my book Why Babywearing Matters too

Hip Dysplasia Institute statement on babywearing and Hip Healthy status