A huge amount of work has been done in recent years to understand the role of soft touch in how babies’ brains develop. Here I summarise the major points in one page!

It has been a great privilege to visit the Affective Touch conference in Liverpool and all the ACE-Aware Nation events in Scotland (with Nadine Burke-Harris and Gabor Mate) and to see all this research coming together.

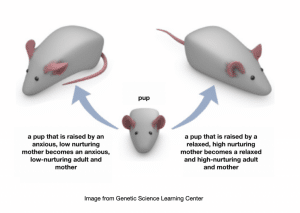

Soft touch changes the DNA and the brain

It switches certain genes on and off, thus affecting cortisol receptor expression and therefore modulates the stress response. This was shown by Michael Meaney and his team; rat pups who were licked and groomed frequently by their mothers became high-licking mothers themselves. The DNA methylation of these high-licking rats and their offspring were different from low-licking rats. When a pup from a low-licking mother was fostered in a high-licking nest, this pup became a high-licker, and was found to display the same DNA changes. Behaviour had altered the expression of these genes, and these epigenetic changes persisted into the offspring.

Soft touch reduces anxiety and pain, thought to be via effects on the HPA axis, parasympathetic system and oxytocin release.

Deep pressure (as in hugs and massage) is also thought to play an important part in social touch, activating brain regions highly similar to those that respond to C-tactile stroking.

Neonatal studies have shown the impact of soft touch (skin to skin) on improving long term neurodevelopmental outcomes, as they are thought provide a scaffold for the developing social brain.

Soft touch and holding is known to help with regulating and stabilising cardiovascular parameters in premature babies and a good case for babywearing as a positive intervention has been made in a study in one NICU.

There are positive long- term effects of supporting early mother-baby close contact. The “Family Nurture Intervention” studies suggest that at age 4-5, the intervention arm showed more healthy autonomic regulation

Soft touch also affects the hormonal systems of the body.

- Oxytocin is well known to be released by skin to skin tactile contact, as well as visual, auditory, olfactory stimuli, and works to promote further social interaction. Close contact stimulates release of this important hormone of bonding into both halves of the dyad (usually mother and baby).

- Oxytocin reduces stress and increases a sense of wellbeing and connection, and it has been proposed that regular skin to skin contact can shift the overall balance of the neurohumoral system away from sympathetic activation (stress, flight/fight) towards the parasympathetic/oxytocinergic system (calm and connection). With what we know about the effects of prolonged stress and cortisol release on health, this is encouraging.

It is clear that there are major benefits to the frontal closeness that babywearing in the early months and years can bring. Of course, soft touch is part of the human experience from birth to old age, and matters at all stages of our lives. The skin is the largest organ of the body, after all!

Further reading

Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior, Nature Neuroscience volume 7, pages 847–854(2004) Meaney et al

C-Tactile Afferents: Cutaneous mediators of oxytocin release during affiliative tactile interactions? Neuropeptides, Volume 64, August 2017, Walker et al

Pleasant Deep Pressure: Expanding the Social Touch Hypothesis Neuroscience, Aug 2020, Case et al

The Dual Nature of Early-Life Experience on Somatosensory Processing in the Human Infant Brain, Current Biology Vol 27 Issue 7, P1048-1054 Maitre et al

Babywearing as an intervention in the NICU Advances in Neonatal Care: September 29, 2020, Williams et al

Longer term effects of nurture on mother/child regulation Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125(4):675-684, Welch et al

Why Oxytocin Matters, Kerstin Uvnas-Moberg, 2020

Neuroendocrine mechanisms involved in the physiological effects caused by skin-to-skin contact. Infant Behavior and Development, Volume 61, November 2020, Uvnas-Moberg et al