Perinatal Mood Disorders and Carrying

The prevalence of Perinatal Mood Disorders (pre and post-natal depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder) is increasing in Western society as it is increasingly fractured and isolated, with a decreased sense of local community and shared care. The birth of a baby is often an overwhelming time for both parents, especially when also faced with the expectations and demands of a fast-paced culture that often judges people by their apparent productivity and appearance. As a GP, I see many families struggling with these conditions that are often diagnosed, and keeping babies close may play a part in surviving these illness, mainly due to the closeness with your child, rather than the choice of sling.

Postnatal depression is on the rise – affecting at least 10-15% of new mothers (with many more sufferers (and fathers) never being recognised to have the condition). Anxiety and PTSD are also worryingly common. Parents are encouraged to put their babies down as much as possible and regain their old lives; babies are expected to learn independence as quickly as possible and stop relying on their parents for their every need.

This approach to caring for children is very new in human history and runs counter to attachment theory, which suggests that the human infant thrives on responsive parenting and close contact.

Read about Ruth’s experience of antenatal depression here; for the rest of this post we will focus mainly on postnatal depression (PND).

What is Postnatal Depression?

Postnatal Depression is a depressive illness which affects between 10 to 15% of new mothers. Many more are never diagnosed with this condition, which can become a very significant issue in the functioning of a family. It is often poorly managed by health care providers, and can be misunderstood by the community and dismissed as “just the baby blues” or “tiredness.” It is common for sufferers to feel very alone and unable to explain just how they feel and why it is so difficult to endure. Prenatal depression is also experienced by many new parents, and postnatal anxiety and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder are also commonly experienced pre and postnatally.

Why is it so common?

Western society is increasingly fractured and isolated, with a decreased sense of local community and shared care. Depression is common in our culture, for reasons not clearly understood, but partly due to the way we live. The birth of a baby is often an overwhelming time for both parents, especially when also faced with the expectations and demands of a fast-paced culture that often judges people by their apparent productivity and appearance.

Before parenthood, people’s identities are often based on their roles and responsibilities in life; work, friendship circles, hobbies and interests. After a baby arrives, this often changes dramatically, sometimes in unexpected ways, and for many, the huge change in the pace of life and the loss of control can be very difficult to deal with. “The burden of conscious responsibility with no let up and the unusual and unexpected degree of fatigue can make a mother feel desperate about whether she can survive and how she will manage.” (Kennell & Klaus) This is the role that community used to play; supporting and carrying each other’s burdens as part of a committed and close-knit group of people who lived together, an experience that few parents enjoy in the West today.

What does it feel like?

Common words used to describe PND are guilt and inadequacy.

“The worst part was the guilt I felt about crying every day when I had a beautiful new daughter.”

“It isn’t about not loving your baby but about feeling overwhelmed with responsibility and unable to cope.”

“My head can feel empty and I have no thoughts.”

“It is just so hard to face another day of feeling totally unlike myself, missing my old life, unable to enjoy this new one.”

Fathers suffer from depression after birth too.

“The first few weeks were the hardest and I would just sit and cry. I felt like this shouldn’t happen to me, I should just be taking it on the chin and getting on with it. But the truth is, I felt alone and without the support of my wife, I would’ve been a lot worse.”

Many parents with PND feel a sense of dissociation and detachment from the child they want to love so much.

“It isn’t about not loving your baby but about feeling overwhelmed with responsibility and unable to cope.”

Caring for people with PND is hard.

“PND is the scariest and loneliest place on the planet and puts a terrible strain on the whole family.”

“My husband felt helpless because he knew something was wrong but I wouldn’t admit it and shut him out. All he could do was try to look after me and be there when I finally admitted it. It caused a lot of irrational arguments.”

What can I do?

If you are suffering, or think you may be suffering from perinatal mood disorders, first be reassured that you are not alone and the vast majority of people with it survive with few long-term ill effects.

Here are some suggestions that may help.

Get help where you are.

Tell your nearest and dearest how you really feel.

“I found the hardest bit was to admit that I wasn’t coping, even when it looked like I was, I was fine on the outside but was a complete mess on the inside.”

Many women testify how supportive their partners and families and close friends are once they understand – ask them to help with the basic jobs of daily life; cooking, cleaning etc. Help them to see how useful you will find it when they listen to you with acceptance and without judgement, and how their understanding when things go wrong is vital. Guilt is a large part of PND and many kind people may inadvertently add to this burden.

Get help from your local health care providers.

This may be your GP, your midwife, your health visitor, your local SureStart centre. The quality of care from these resources can vary enormously. It can help to write down on paper how you feel in advance and what you think you need (validation, formal counselling, CBT or medication, for example) and take it with you to appointments. Continuity of care is great, if available; a HCP who listens and cares can make a greater difference than one who fires questions and is keen to tick boxes and prescribe medication at once.

“Guilt and lack of confidence are so typical of PND and my HCP was essentially validating those feelings even though objectively I was doing a great job!”

Be armed with information (e.g. if you wish to carry breastfeeding, sertraline is safe in these circumstances). The Breastfeeding Network is a valuable resource. If you are not satisfied with the care you are receiving, find different care.

Get help from your local non-NHS resources.

These can be very useful, such as HomeStart (a befriending service) and local PND groups. A postnatal doula may help, and there are many national helplines and resources (see below)

Get help from online social resources.

There are many forums and parenting groups full of people who know how you feel, and will listen and share. Being among people with the same values and parenting beliefs may be a source of great encouragement. Equally, avoid too much time online.

Get out!

It can be very hard to actually get out of the house when struggling with dark thoughts or hopelessness, but it is worth the effort involved. Even a walk down the road is a good start, and encourages release of endorphins (the natural feel-good hormone). Arrange to meet some friends, and ask them to encourage you to come. Try to make a plan for most days, and be kind to yourself if you decide on a pyjama day instead. Try to arrange some time to spend alone with your other half, to remember who you still are, as well as parents.

Get nourishment.

Good quality food, drink, exercise and sleep are vital to your own health and sanity, as are times to enjoy the things you used to. Dress well in bright mood-enhancing colours. You are still a person and your own needs should be met as much as your child’s. Some people make use of night-time carers to allow some much-needed uninterrupted sleep.

Get past your birth story.

For many women, recovering from birth takes a while, especially if it was not the hoped-for experience. The NHS Afterthoughts service and counselling can help if you feel a sense of grief.

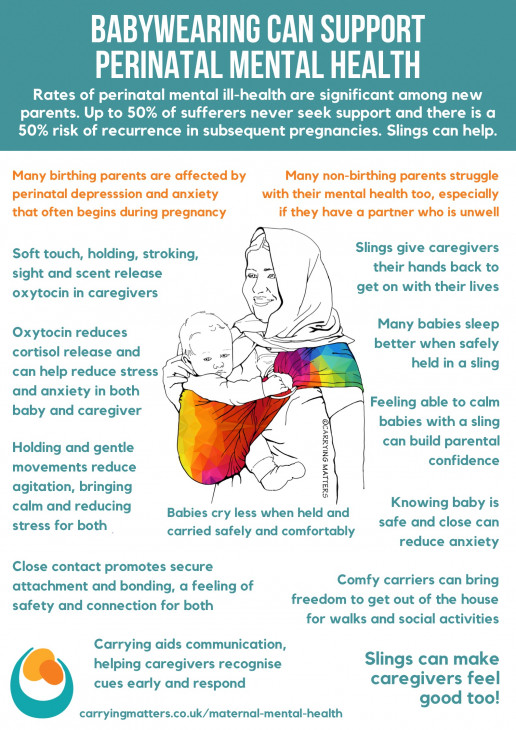

Get a sling or carrier.

Keeping your baby physically close is well known to stimulate the release of oxytocin. Oxytocin is a hormone that is closely related to bonding and attachment. It is released during labour and breastfeeding, and, crucially, during skin-to-skin contact and social interaction. It has an important role in encouraging nurturing feelings and a sense of belonging, and reduces anxiety and depression by affecting cortisol release.

Babies who are in close contact with their parents have been shown to have a corresponding higher level of oxytocin than their non-carried counterparts; which subsequently helps to reduce baby’s own stress levels and improve their sense of secure attachment; their needs are met at the point of request. Calmer babies are easier to care for; win/win.

The soft touch of close skin to skin contact reduces the release of cortisol, the stress hormone, via C afferet fibres affecting receptors in the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis. Stroking has been shown to reduce pain responses.

Modern life is fast-paced and for many, constant carrying of ever-growing children can be difficult to achieve, or uncomfortable after the travails of birth. This is where the practice of using a sling, (sometimes known as babywearing) can be of great value. A soft sling that allows you to keep your child close to you, (thereby stimulating the release of oxytocin and reducing cortisol), and helps your baby to relax and sleep in secure comfort may make a huge difference to your life and your feelings and help you to feel that you can cope. Anxiety may settle a little as you know your little one is safe next to you.

“The sling brought us back to an almost pregnant-like state, with him a part of me, listening to one another’s cues. He was calmer for being close to me, which made me feel more confident, which brightened my mood. Leaving the house felt less daunting so I got more exercise and again increased my confidence. I talked to him more, whether he was awake or not, and he became my son rather than a tiny scary stranger.”

“My favourite thing in the whole world, that never fails to calm me or lift my mood has been cuddles with my baby, particularly skin-to-skin. For me, there is no antidepressant like it.”

“When she was in her pram I felt completely removed from her and her world. I was just an accessory, she was a job to do and I was irrelevant. Using a sling finally helped me bond properly with her and made a massive difference to the PND.”

Many slings are extremely comfortable to use, and can be very practical indeed. It is possible to learn how to feed discreetly in a sling, allowing you more flexibility about being out of the house for the day with your baby.

Slings give you and your baby the freedom to be on the move together, rather than feeling stuck; to go out into the world for a walk or go shopping without struggling with the complexities of a pram. Movement and exercise are vital to wellbeing; and using a sling safely can help your body recover from birth and become stronger.

Slings can be beautiful and colour therapy can help to lift the mood. Learning a new skill can be therapeutic, and many parents find a great sense of community among other sling users both locally and online. This can help with feelings of isolation, especially if you have chosen to parent differently from your family or your peers.

Get a sense of perspective.

What matters in these early months is you and your baby. It does not matter what other people think; the house does not need to be pristine, you do not need to impress people with how well you are taking to parenthood. I have heard many women describe how they “are falling apart on the inside”.

“I thought because I wasn’t suicidal or not looking after things that it couldn’t be PND so held back for a long time from accepting it and getting help.”

“I found the hardest bit was to admit that I wasn’t coping, even when it looked like I was, I looked fine on the outside but was a complete mess on the inside.”

Get confident again.

Reflect on what you have achieved so far and use that to build self-belief. Learn to trust yourself, be an instinctive parent – and you will fin that as you encourage others, you will find yourself lifted too. Some people find going back to work can be very helpful; the chance to use skills again and have adult interactions once more can be a great boost to self-confidence.

Useful Resources

Postnatal Depression Information Leaflet

Postnatal Depression Information Leaflet 2

Pre and Postnatal Depression Advice and Support (PANDAS)

Mothers for Mothers Postnatal Depression Support

Postnatal Illness Information (PNI)

The Impact of Babywearing on Mothers’ Mental Health – Aimee Gourlay

Further Reading

“I carry my heart in a sling” – a blog on how slings helped Lindsay fight her PND.

Sling Sally’s talk on Slings and Sanity for the 2015 Northern Sling Exhibition

Surviving PostNatal Depression – Selina Shaik for MIND

How Carrying Helped My Recovery – Ellie at Peekaboo Slings

Carrying With A Mental Health Disorder – Andrea’s story

The unhelpful "rules" of babywearing

There are so many unhelpful rules of babywearing. I'm not talking about basic safety guidelines, but about the unspoken rules about how things must be done.This needs addressing. I love babywearing. I love how special it is. I love how empowering and enabling it can be and what a difference it can make to children and their carers and the society around them.

I also love that it just makes life work for so many people on a practical level, regardless of all the benefits and reasons about why it is an activity that matters. Babywearing may be magical for many, and has so many positive effects on a physiological and neurological level, but really, for some, it’s just about getting stuff done, keeping the cogwheels of daily life turning, or helping to survive very tough situations.

I have watched thousands of people carrying their children all around the world and I love that I am part of a tradition of child rearing that goes back beyond the history books into our anthropological origins. I love it so much that I wrote a book all about it!

Carrying children is normal human behaviour, and it isn’t, and shouldn’t be, complicated or difficult. It shouldn’t be scary, inaccessible or expensive. It does not belong to groups of people to “own” or to build tall walls around to make things secret or elitist. Babywearing (the use of a sling or carrier to keep a child safe and close to a parent) is for everyone, every gender, every colour, every ability, every size, every shape. Babywearing should bring us together, not divide us. It should not alienate or exclude entire groups of people.

However, as the practice becomes more mainstream and the industry grows, this alienation is unfortunately happening more and more often. Marketing campaigns and the general make-up of many babywearing groups suggests that this is an activity for relatively well-off middle class “standard sized” white women in nuclear families, carrying able-bodied and healthy children. This is a direction that needs to be arrested before it becomes too entrenched. I’ll say it again, babywearing is for everyone and can be done in so many ways.

One way that babywearing can become elitist is in the development of complex rules, and I’d like to have a discussion about some of these “rules” and “guides” of babywearing that I am seeing shared around. I understand that it can feel reassuring to have black and white lists of what you can and can’t do, and schedules for certain types of carrying. These can act as a framework for where to begin with using a sling. This is valuable, especially as many of us have lost the shared collective wisdom that comes from living in communities and no longer learn how to parent from the people living around us. Many of us turn to books and to the internet and ask for guidance.

However, I think these “rules” often end up making things harder and disempowering the very people who need the most support. Here are some common examples.

Some commonly stated "Rules"

- Do not use a stretchy wrap beyond three months

- Do not back carry with a stretchy wrap

- Do not use a soft structured carrier for a newborn

- Do not do any form of sideways cradle carry

- Do not use a narrow based carrier

- Do not face your child out in a carrier

- Do not back carry a baby before they can sit unaided

- Do not back carry a newborn in a ring sling

- Low back carries are dangerous, high back carries are much better

- Once your baby is walking you must begin to use a toddler-size carrier

- Bigger children must be carried on the back

- Do not use footed pyjamas for babies in slings

I could go on…

These rules can be useful, but often they exclude significant proportions of the population. You can use a stretchy wrap to carry an older child, if they are safe and comfy. You can use your stretchy wrap in many ways, including on the back, if your child is safe and comfy. You can use a soft structured carrier for a newborn, if it fits them and is safe and comfy. You can carry a child in a sideways seated position or even a cradle carry, and facing out, if they are safe and comfy. You can use a narrow based carrier for a baby or a baby sized carrier for a toddler, if they are safe and comfy. You can carry a baby on your back in any form of carrier if they are safe and comfy. You can carry any age baby on your back or your front if they are safe and comfy. You can carry your child who is wearing footed pyjamas if the child is safe and comfy (ie their toes have room to wiggle). You can carry your child whatever size you are. In fact, you can do pretty much anything you want to do, if your baby is safe and comfy.

Do you get the theme?

Is your baby safe and comfy? Do you feel confident caring for your child with your carrier? Then carry right on!

I think the only “rules” when it comes to carrying a child in any form of sling are

- Can they breathe safely and without any obstruction at all times?

- Are they being held safely and securely in a carrier that fits (to ensure they are able to breathe easily and cannot slump into a position that would obstruct their airway)?

- Are they as comfortable as the circumstances allow?

How do you check if a child is breathing safely in the carrier?

- Look at them, listen to them, be aware of them.

- Check their airways are free of any fabric and they are not slumping or folded over with their ribcage compressed and chin on the chest.

How do you ensure they are safe and snug in the carrier and that it fits?

- A well fitting carrier holds a child close to the parent, close enough that if the parent leans forwards, the child does not swing free. This helps to avoid slumping over in the carrier.

- If a child’s body can slump, the carrier does not fit or is not tight enough.

- The “knee to knee” rule is often overstated in its importance for older children (the M shape can be protective for children at risk of hip dysplasia in the early months.)

How do you ensure they are comfortable in the carrier?

- This is all about being responsive and connected to the child being carried.

- They should fit inside the carrier, be able to breathe safely, and should not be too hot (overheated babies are more likely to stop breathing).

- Check on your child, be aware of their experience and how they are behaving in the carrier. The more you interact with your child the more you will know that they are OK (or not!)

If your baby is safe, able to breathe and is comfortable, and you feel confident that all is well, then it probably is well. Carry right on! And if you would like some encouragement, find a friendly educator and help them learn how to support you in a way that builds you up and keeps you carrying happily.

Real life is lived in the grey areas, in between the black and white.

It is important to remember that every child and every parent has different needs. Parents of twins may need to be able to back carry one twin from a very early age, to be able to cope with family life. They may choose to use a buckle carrier on the back, and if the child is able to breathe safely and is not uncomfortable then that makes their lives work. Telling them this is forbidden creates needless barriers and makes life harder. A stretchy wrap for a one year old may not be as comfortable as a woven wrap, but for a parent on a budget who now has a less-unhappy toddler held close while the baby can be cleaned, this is a win-win situation. A four month old who will will only tolerate facing out in a narrow based carrier can be happily transported on a school run. Millions of women around the world have carried young babies in low torso carries with simple pieces of cloth. A disabled child who cannot sit unaided can be held safely and securely on the back in several types of carrier which will definitely make everything much easier. Do be aware of how your language and how you educate can affect others and significantly disempower people.

“Oh, but these rules are for normal people!” This is a common dismissal of any criticism of “rules” and is unbelievably inappropriate. Our society is made up of people of all abilities and all skills. More than one billion people in today’s world have a disability; that’s 15% of the population. This ratio may not be reflected in the proportion of children who are brought to babywearing groups, just like people of colour are missing from these gatherings. The fault is not theirs; it is ours. We must be more inclusive and we must make efforts to reach out to people. Just imagine how different things could be, if some of these walls of prejudice were pulled down from the inside.

Grainne and Tessa are a great example of how babywearing can actually empower beyond the “rules.” Little Tessa was born without a nose (arhinia) and had to have a tracheostomy when she was very young. Her family were told that she was safest to be sleeping in a separate room with various wires and monitors attached to her for any alerts in a change of breathing. In fact, Grainne decided to wear Tessa in a sling, keeping her close and safe and visible at all times; if Tessa stopped breathing, Grainne would see it and feel it as it happened, thanks to the sling (read more about them here.) The sling made life work for them, and also made it much happier during some very tough times. Common sense, knowledge of safety and a willingness to bend the rules worked together to enhance their lives, when they could so easily have missed out.

This is a superb blog for further reading; all about ableism in the babywearing community and I urge you to read it.

http://bindungtraegt.de/ableismback-wearing/

Please also read the Tania Talks blog posts on babywearing (she is a wheelchair user)

https://www.whentaniatalks.com/the-realities-of-back-carrying-as-a-wheelchair-user/

https://www.whentaniatalks.com/back-carrying-as-a-wheelchair-user/

When the time comes to stop carrying....

There will come a time when you stop carrying your child. This is likely to bring very mixed emotions.

Our lives as parents are full of the most exciting and precious “firsts”; the first flutter, the first cry, the first kiss. Then comes the first feed, the first smile, the first word, the first steps. Not all firsts are delightful, of course… but at least there is some relief in getting some of these hurdles done and dusted; the first injury, the first day at nursery, the first day at big school..

Inevitably, there are “lasts” too. Sometimes these are planned and some are welcomed; the last injection, the last day at pre-school before the long holidays, the last day in a plaster cast. Many “lasts” creep up on us unnoticed, which is a mercy; would you want to know that tomorrow your child would no longer ask for milk, that yesterday was the last time your child would agree to hold your hand in public, or that you’d just carried your child in your arms for the last time? It’s inevitable… our tiny babies grow bigger, and they just don’t stop growing, until before we know it, we have toddlers, and then pre-schoolers, and then school-age kids, teenagers, and one day our children will have children of their own.

All parents stop carrying their children eventually, for many reasons.

- Some stop soon after birth, because they feel their bodies aren’t strong enough and that their baby is too heavy (this is usually just a matter of finding the right sling to be comfy and supportive, getting muscles used to it and then carrying daily. Many families carry toddlers and preschoolers in slings with great happiness and in comfort. Do go and see your local sling library for help.

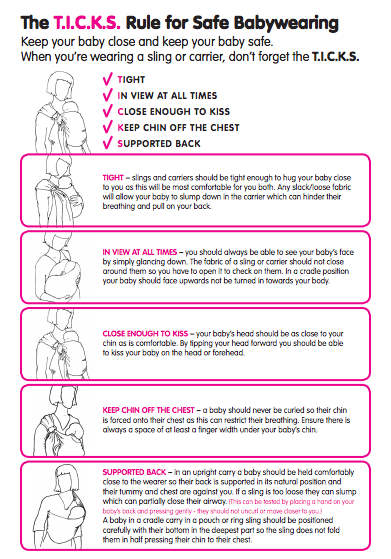

- Some may stop out of fear that the sling isn’t on right or isn’t safe. It is good to be safe and to know how to use your sling well; this is where sling libraries and consultants come in. They can help you build your confidence and keep you carrying happily. See the TICKS guidelines and “Sling Safety” for more.

- Others may stop out of fear that too much carrying will spoil a child and make them clingy (for a full discussion of the cultural misconceptions behind this please see here – “Do Slings Make Children Clingy?”). In summary; a sling won’t spoil your child and will actually help their emotional development.

- Still others will stop because their baby doesn’t seem to enjoy being in a sling at all. This can be easy to sort out (see “Help! My child cries in the sling” for some further reassurance and troubleshooting).

- Some will stop because a child who has previously been happy is now wriggling and pushing away and it seems that they have outgrown the carrier (this is often due to visibility issues, which can be easy to fix – options such as hip carries, back carries can be very useful. Do go and see your local sling resource for help.)

- Some will stop because their child is now able to walk and “no longer needs carrying…” This isn’t true, big kids like to be carried too! Some toddlers will go on “sling strike” for a while as they want to explore their new skills of walking and many will come back to the cuddle of the carrier when they are ready, on their own terms. It is usually best to be guided by your child.

And finally – some will stop because their older child no longer wishes or needs to be carried; and this is where my daughter and I are now. I cannot carry my son any more; he is eight years old and hefty and I am just not strong enough (I still hold his hand as he drifts off to sleep every night, long may it last – every chance for connection is so precious). My little big girl is 5 and started school in September, she is still light and portable, but she really doesn’t want carrying much these days. We carry in arms and with piggybacks more than slings, probably, but from time to time when she is tired or overwhelmed, she will ask for a carrier; and specifies which one too. The ring sling (purple, please!!!).. the clip one (no, not that one, THAT one!)… or the wrap (on the front today, Mummy.. no, on the back! no, front, haha! Can we have the Elsa one today? Oh, there’s a new wrap, can I have a sweet if you want a go Mummy?) She really surprised me by asking for a sling almost every day of our last summer holiday; probably as I wasn’t working and was therefore more “available” to carry her and she wanted to make the most of it. I loved every last second of each snuggle, being wistfully aware that our carrying days are numbered.

She’s been in slings all her life, since she was a newborn. It hasn’t harmed or slowed her development; she crawled and walked and ran at the expected ages, is fiercely independent and is often a speck in the distance running far ahead. She is strong and lithe and fast on her feet. She sleeps all night in her own bed. She sings all day long and she sings herself to sleep; and I am convinced the slings played their part in our family journey together.

I’ve used slings that I chose both for their comfort and their beauty, and we have enjoyed great happiness in them together. But they have also brought us great value beyond their functionality. The slings have allowed us to be connected physically for far longer than would otherwise be possible with only-in-arms carrying. They have helped us to bond and to communicate (I am deaf and have to lipread), they helped us to recover from illness or sadness, they have allowed us to explore our glorious Peak countryside off the beaten track.

The closeness and security she has gained from knowing she can be held close when she needs it has given her freedom and self-confidence; a rock solid foundation from which to explore the world. It was easy to talk to strangers from the sling as she was at an equal height rather than always being small and looked down-on, and now that she stands on her own two feet looking up at people, her assured friendliness continues (as many visitors to our house will testify!)

I will be forever grateful for the role our slings have played in family life; and each carry now is tinged with nostalgia. One day it will have been the last time. Until then, I will carry her whenever she asks, and enjoy every single second.